What New Styles of Art Were Developed During the Renaissance

Renaissance art (1350 - 1620 AD[ane]) is the painting, sculpture, and decorative arts of the flow of European history known equally the Renaissance, which emerged as a distinct style in Italy in well-nigh Advert 1400, in parallel with developments which occurred in philosophy, literature, music, science, and applied science. Renaissance art took as its foundation the art of Classical antiquity, perceived as the noblest of ancient traditions, but transformed that tradition past arresting recent developments in the art of Northern Europe and past applying contemporary scientific cognition. Along with Renaissance humanist philosophy, it spread throughout Europe, affecting both artists and their patrons with the development of new techniques and new artistic sensibilities. For art historians, Renaissance fine art marks the transition of Europe from the medieval flow to the Early Modernistic age.

The body of art, painting, sculpture, architecture, music, and literature identified equally "Renaissance art" was primarily produced during the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries in Europe under the combined influences of an increased awareness of nature, a revival of classical learning, and a more individualistic view of human. Scholars no longer believe that the Renaissance marked an precipitous break with medieval values, as is suggested by the French give-and-take renaissance, literally meaning "rebirth". Rather, historical sources suggest that involvement in nature, humanistic learning, and individualism were already nowadays in the late medieval period and became dominant in 15th- and 16th-century Italy, meantime with social and economic changes such as the secularization of daily life, the rise of a rational money-credit economy, and greatly increased social mobility. In many parts of Europe, Early on Renaissance art was created in parallel with Belatedly Medieval art.

Origins [edit]

Many influences on the evolution of Renaissance men and women in the early 15th century take been credited with the emergence of Renaissance art; they are the aforementioned equally those that afflicted philosophy, literature, architecture, theology, science, authorities and other aspects of order. The following list presents a summary of changes to social and cultural atmospheric condition which take been identified every bit factors which contributed to the development of Renaissance art. Each is dealt with more fully in the main manufactures cited above. The scholars of Renaissance period focused on present life and means to make human life evolve and amend in its entirety. They did not pay much attention to medieval philosophy or faith. During this period, scholars and humanists like Erasmus, Dante and Petrarch criticized superstitious behavior and also questioned them. [ii] The concept of didactics as well widened its spectrum and focused more than on creating 'an ideal man' who would have a off-white agreement of arts, music, poetry and literature and would have the ability to appreciate these aspects of life. During this flow, there emerged a scientific outlook which helped people question the needless rituals of the church.

- Classical texts, lost to European scholars for centuries, became available. These included documents of philosophy, prose, verse, drama, science, a thesis on the arts, and early on Christian theology.

- Europe gained access to advanced mathematics, which had its provenance in the works of Islamic scholars.

- The advent of movable type printing in the 15th century meant that ideas could be disseminated easily, and an increasing number of books were written for a broader public.

- The establishment of the Medici Banking company and the subsequent trade it generated brought unprecedented wealth to a single Italian city, Florence.

- Cosimo de' Medici prepare a new standard for patronage of the arts, not associated with the church building or monarchy.

- Humanist philosophy meant that man'south relationship with humanity, the universe and God was no longer the exclusive province of the church building.

- A revived involvement in the Classics brought about the kickoff archaeological study of Roman remains by the architect Brunelleschi and sculptor Donatello. The revival of a style of architecture based on classical precedents inspired a corresponding classicism in painting and sculpture, which manifested itself as early as the 1420s in the paintings of Masaccio and Uccello.

- The comeback of oil paint and developments in oil-painting technique past Belgian artists such equally Robert Campin, Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden and Hugo van der Goes led to its adoption in Italy from most 1475 and had ultimately lasting furnishings on painting practices worldwide.

- The serendipitous presence inside the region of Florence in the early on 15th century of certain individuals of artistic genius, most notably Masaccio, Brunelleschi, Ghiberti, Piero della Francesca, Donatello and Michelozzo formed an ethos out of which sprang the peachy masters of the High Renaissance, also as supporting and encouraging many lesser artists to achieve work of extraordinary quality.[3]

- A like heritage of artistic achievement occurred in Venice through the talented Bellini family unit, their influential in-law Mantegna, Giorgione, Titian and Tintoretto.[three] [4] [5]

- The publication of two treatises by Leone Battista Alberti, De pictura ("On Painting") in 1435 and De re aedificatoria ("Ten Books on Architecture") in 1452.

History [edit]

Proto-Renaissance in Italian republic, 1280–1400 [edit]

In Italia in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, the sculpture of Nicola Pisano and his son Giovanni Pisano, working at Pisa, Siena and Pistoia shows markedly classicising tendencies, probably influenced past the familiarity of these artists with ancient Roman sarcophagi. Their masterpieces are the pulpits of the Baptistery and Cathedral of Pisa.

Gimmicky with Giovanni Pisano, the Florentine painter Giotto developed a mode of figurative painting that was unprecedentedly naturalistic, iii-dimensional, lifelike and classicist, when compared with that of his contemporaries and instructor Cimabue. Giotto, whose greatest piece of work is the wheel of the Life of Christ at the Arena Chapel in Padua, was seen by the 16th-century biographer Giorgio Vasari as "rescuing and restoring fine art" from the "crude, traditional, Byzantine manner" prevalent in Italy in the 13th century.

Early Renaissance in Italy, 1400–1495 [edit]

Donatello, David (1440s?) Museo Nazionale del Bargello.

Although both the Pisanos and Giotto had students and followers, the first truly Renaissance artists were not to emerge in Florence until 1401 with the competition to sculpt a prepare of bronze doors of the Baptistery of Florence Cathedral, which drew entries from 7 immature sculptors including Brunelleschi, Donatello and the winner, Lorenzo Ghiberti. Brunelleschi, near famous as the architect of the dome of Florence Cathedral and the Church of San Lorenzo, created a number of sculptural works, including a life-sized crucifix in Santa Maria Novella, renowned for its naturalism. His studies of perspective are thought to accept influenced the painter Masaccio. Donatello became renowned as the greatest sculptor of the Early Renaissance, his masterpieces being his humanist and unusually erotic statue of David, 1 of the icons of the Florentine democracy, and his great monument to Gattamelata, the first large equestrian bronze to be created since Roman times.

The contemporary of Donatello, Masaccio, was the painterly descendant of Giotto and began the Early Renaissance in Italian painting in 1425, furthering the trend towards solidity of grade and naturalism of face and gesture that Giotto had begun a century earlier. From 1425–1428, Masaccio completed several console paintings but is all-time known for the fresco cycle that he began in the Brancacci Chapel with the older artist Masolino and which had profound influence on later painters, including Michelangelo. Masaccio's developments were carried forrad in the paintings of Fra Angelico, particularly in his frescos at the Convent of San Marco in Florence.

The handling of the elements of perspective and light in painting was of item business concern to 15th-century Florentine painters. Uccello was and so obsessed with trying to accomplish an appearance of perspective that, according to Giorgio Vasari, it disturbed his sleep. His solutions can exist seen in his masterpiece set of 3 paintings, the Battle of San Romano, which is believed to have been completed past 1460. Piero della Francesca made systematic and scientific studies of both light and linear perspective, the results of which tin can be seen in his fresco bike of The History of the Truthful Cantankerous in San Francesco, Arezzo.

In Naples, the painter Antonello da Messina began using oil paints for portraits and religious paintings at a date that preceded other Italian painters, perchance about 1450. He carried this technique north and influenced the painters of Venice. I of the most significant painters of Northern Italy was Andrea Mantegna, who decorated the interior of a room, the Camera degli Sposi for his patron Ludovico Gonzaga, setting portraits of the family unit and court into an illusionistic architectural space.

The end period of the Early Renaissance in Italian art is marked, like its beginning, by a particular commission that drew artists together, this fourth dimension in cooperation rather than competition. Pope Sixtus IV had rebuilt the Papal Chapel, named the Sistine Chapel in his honour, and deputed a grouping of artists, Sandro Botticelli, Pietro Perugino, Domenico Ghirlandaio and Cosimo Rosselli to decorate its wall with fresco cycles depicting the Life of Christ and the Life of Moses. In the xvi large paintings, the artists, although each working in his individual style, agreed on principles of format, and utilised the techniques of lighting, linear and atmospheric perspective, anatomy, foreshortening and characterisation that had been carried to a high point in the large Florentine studios of Ghiberti, Verrocchio, Ghirlandaio and Perugino.

Early on Netherlandish fine art, 1425–1525 [edit]

The painters of the Depression Countries in this period included Jan van Eyck, his brother Hubert van Eyck, Robert Campin, Hans Memling, Rogier van der Weyden and Hugo van der Goes. Their painting developed partly independently of Early Italian Renaissance painting, and without the influence of a deliberate and conscious striving to revive antiquity.

The style of painting grew directly out of medieval painting in tempera, on panels and illuminated manuscripts, and other forms such as stained glass; the medium of fresco was less common in northern Europe. The medium used was oil paint, which had long been utilised for painting leather ceremonial shields and accoutrements because it was flexible and relatively durable. The earliest Netherlandish oil paintings are meticulous and detailed like tempera paintings. The cloth lent itself to the depiction of tonal variations and texture, and so facilitating the observation of nature in great detail.

The Netherlandish painters did non approach the cosmos of a picture through a framework of linear perspective and right proportion. They maintained a medieval view of hierarchical proportion and religious symbolism, while delighting in a realistic treatment of material elements, both natural and human being-made. January van Eyck, with his brother Hubert, painted The Altarpiece of the Mystical Lamb. Information technology is likely that Antonello da Messina became familiar with Van Eyck's work, while in Naples or Sicily. In 1475, Hugo van der Goes' Portinari Altarpiece arrived in Florence, where it was to have a profound influence on many painters, most immediately Domenico Ghirlandaio, who painted an altarpiece imitating its elements.

A very meaning Netherlandish painter towards the finish of the period was Hieronymus Bosch, who employed the type of fanciful forms that were often utilized to decorate borders and letters in illuminated manuscripts, combining found and beast forms with architectonic ones. When taken from the context of the illumination and peopled with humans, these forms requite Bosch'south paintings a surreal quality which take no parallel in the piece of work of whatsoever other Renaissance painter. His masterpiece is the triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights.

Early Renaissance in France, 1375–1528 [edit]

The artists of France (including duchies such every bit Burgundy) were often associated with courts, providing illuminated manuscripts and portraits for the nobility as well as devotional paintings and altarpieces. Among the well-nigh famous were the Limbourg brothers, Flemish illuminators and creators of the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry manuscript illumination. Jean Fouquet, painter of the regal court, visited Italy in 1437 and reflects the influence of Florentine painters such every bit Paolo Uccello. Although best known for his portraits such equally that of Charles VII of France, Fouquet also created illuminations, and is thought to be the inventor of the portrait miniature.

There were a number of artists at this date who painted famed altarpieces, that are stylistically quite distinct from both the Italian and the Flemish. These include two enigmatic figures, Enguerrand Quarton, to whom is ascribed the Pieta of Villeneuve-lès-Avignon, and Jean Hey, otherwise known as "the Master of Moulins" after his most famous work, the Moulins Altarpiece. In these works, realism and close observation of the man effigy, emotions and lighting are combined with a medieval formality, which includes gilt backgrounds.

Loftier Renaissance in Italy, 1495–1520 [edit]

The "universal genius" Leonardo da Vinci was to farther perfect the aspects of pictorial fine art (lighting, linear and atmospheric perspective, anatomy, foreshortening and characterisation) that had preoccupied artists of the Early Renaissance, in a lifetime of studying and meticulously recording his observations of the natural world. His adoption of oil pigment as his primary media meant that he could depict calorie-free and its effects on the landscape and objects more than naturally and with greater dramatic event than had ever been washed before, as demonstrated in the Mona Lisa (1503–1506). His dissection of cadavers carried forward the understanding of skeletal and muscular anatomy, every bit seen in the unfinished Saint Jerome in the Wilderness (c. 1480). His delineation of human being emotion in The Concluding Supper, completed 1495–1498, fix the benchmark for religious painting.

The fine art of Leonardo'southward younger contemporary Michelangelo took a very different direction. Michelangelo in neither his painting nor his sculpture demonstrates any interest in the observation of any natural object except the man trunk. He perfected his technique in depicting information technology, while in his early twenties, past the creation of the enormous marble statue of David and the group Pietà, in the St Peter'south Basilica, Rome. He so set about an exploration of the expressive possibilities of the human anatomy. His commission by Pope Julius 2 to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling resulted in the supreme masterpiece of figurative composition, which was to have profound effect on every subsequent generation of European artists.[6] His later piece of work, The Last Judgement, painted on the chantry wall of the Sistine Chapel between 1534 and 1541, shows a Mannerist (also called Late Renaissance) style with generally elongated bodies which took over from the High Renaissance style between 1520 and 1530.

Standing alongside Leonardo and Michelangelo as the 3rd great painter of the High Renaissance was the younger Raphael, who in a short lifespan painted a cracking number of life-like and engaging portraits, including those of Pope Julius II and his successor Pope Leo X, and numerous portrayals of the Madonna and Christ Child, including the Sistine Madonna. His expiry in 1520 at age 37 is considered past many art historians to exist the finish of the High Renaissance period, although some private artists continued working in the High Renaissance style for many years thereafter.

In Northern Italian republic, the Loftier Renaissance is represented primarily by members of the Venetian school, peculiarly by the latter works of Giovanni Bellini, especially religious paintings, which include several large altarpieces of a type known every bit "Sacred Chat", which evidence a grouping of saints around the enthroned Madonna. His contemporary Giorgione, who died at about the historic period of 32 in 1510, left a small number of enigmatic works, including The Tempest, the subject of which has remained a matter of speculation. The primeval works of Titian date from the era of the Loftier Renaissance, including a massive altarpiece The Assumption of the Virgin which combines man activeness and drama with spectacular colour and temper. Titian continued painting in a generally High Renaissance way until virtually the end of his career in the 1570s, although he increasingly used colour and light over line to define his figures.

German Renaissance fine art [edit]

German Renaissance art falls into the broader category of the Renaissance in Northern Europe, also known as the Northern Renaissance. Renaissance influences began to appear in High german fine art in the 15th century, just this trend was not widespread. Gardner's Art Through the Ages identifies Michael Pacher, a painter and sculptor, equally the first German creative person whose work begins to prove Italian Renaissance influences. According to that source, Pacher'due south painting, St. Wolfgang Forces the Devil to Hold His Prayerbook (c. 1481), is Tardily Gothic in style, but also shows the influence of the Italian artist Mantegna.[7]

In the 1500s, Renaissance fine art in Frg became more common as, co-ordinate to Gardner, "The art of northern Europe during the sixteenth century is characterized by a sudden awareness of the advances made past the Italian Renaissance and past a desire to assimilate this new mode as rapidly as possible."[8] One of the best known practitioners of High german Renaissance art was Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), whose fascination with classical ideas led him to Italia to written report fine art. Both Gardner and Russell recognized the importance of Dürer's contribution to High german art in bringing Italian Renaissance styles and ideas to Germany.[9] [10] Russell calls this "Opening the Gothic windows of German language art,"[9] while Gardner calls it Dürer's "life mission."[10] Importantly, equally Gardner points out, Dürer "was the get-go northern artist who fully understood the basic aims of the southern Renaissance,"[10] although his style did not ever reflect that. The aforementioned source says that Hans Holbein the Younger (1497–1543) successfully alloyed Italian ideas while also keeping "northern traditions of close realism."[xi] This is contrasted with Dürer's tendency to work in "his own native High german way"[10] instead of combining German and Italian styles. Other of import artists of the German Renaissance were Matthias Grünewald, Albrecht Altdorfer and Lucas Cranach the Elder.[12]

Artisans such as engravers became more concerned with aesthetics rather than just perfecting their crafts. Germany had master engravers, such equally Martin Schongauer, who did metal engravings in the tardily 1400s. Gardner relates this mastery of the graphic arts to advances in printing which occurred in Germany, and says that metallic engraving began to replace the woodcut during the Renaissance.[thirteen] Nonetheless, some artists, such as Albrecht Dürer, continued to do woodcuts. Both Gardner and Russell describe the fine quality of Dürer's woodcuts, with Russell stating in The World of Dürer that Dürer "elevated them into high works of art."[9]

United kingdom [edit]

Britain was very tardily to develop a distinct Renaissance style and about artists of the Tudor court were imported foreigners, normally from the Low Countries, including Hans Holbein the Younger, who died in England. I exception was the portrait miniature, which artists including Nicholas Hilliard developed into a distinct genre well before it became popular in the residuum of Europe. Renaissance fine art in Scotland was similarly dependent on imported artists, and largely restricted to the court.

Themes and symbolism [edit]

Renaissance artists painted a wide multifariousness of themes. Religious altarpieces, fresco cycles, and pocket-sized works for private devotion were very popular. For inspiration, painters in both Italy and northern Europe frequently turned to Jacobus de Voragine'due south Aureate Legend (1260), a highly influential source book for the lives of saints that had already had a potent influence on Medieval artists. The rebirth of classical antiquity and Renaissance humanism also resulted in many mythological and history paintings. Ovidian stories, for case, were very popular. Decorative decoration, often used in painted architectural elements, was especially influenced by classical Roman motifs.

Techniques [edit]

- The employ of proportion – The offset major treatment of the painting as a window into space appeared in the work of Giotto di Bondone, at the beginning of the 14th century. True linear perspective was formalized later, by Filippo Brunelleschi and Leon Battista Alberti. In addition to giving a more than realistic presentation of fine art, it moved Renaissance painters into composing more paintings.

- Foreshortening – The term foreshortening refers to the creative issue of shortening lines in a cartoon so as to create an illusion of depth.

- Sfumato – The term sfumato was coined by Italian Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci and refers to a fine art painting technique of blurring or softening of sharp outlines past subtle and gradual blending of i tone into some other through the use of sparse glazes to requite the illusion of depth or three-dimensionality. This stems from the Italian give-and-take sfumare significant to evaporate or to fade out. The Latin origin is fumare, to fume.

- Chiaroscuro – The term chiaroscuro refers to the fine art painting modeling result of using a strong contrast between light and dark to give the illusion of depth or three-dimensionality. This comes from the Italian words pregnant light (chiaro) and dark (scuro), a technique which came into broad apply in the Bizarre menstruation.

List of Renaissance artists [edit]

Italy [edit]

- Giotto di Bondone (1267–1337)

- Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446)

- Masolino (c. 1383 – c. 1447)

- Donatello (c. 1386 – 1466)

- Pisanello (c. 1395 – c. 1455)

- Fra Angelico (c. 1395 – 1455)

- Paolo Uccello (1397–1475)

- Masaccio (1401–1428)

- Leone Battista Alberti (1404–1472)

- Filippo Lippi (c. 1406 – 1469)

- Domenico Veneziano (c. 1410 – 1461)

- Piero della Francesca (c. 1415 – 1492)

- Andrea del Castagno (c. 1421 – 1457)

- Benozzo Gozzoli (c. 1421 – 1497)

- Alessio Baldovinetti (1425–1499)

- Antonio del Pollaiuolo (1429 - 1498)

- Antonello da Messina (c. 1430 – 1479)

- Giovanni Bellini (c.1430 - 1516)

- Andrea Mantegna (c. 1431 – 1506)

- Andrea del Verrocchio (c. 1435 – 1488)

- Giovanni Santi (1435–1494)

- Carlo Crivelli (c. 1435 – c. 1495)

- Donato Bramante (1444 - 1514)

- Sandro Botticelli (c. 1445 – 1510)

- Luca Signorelli (c. 1445 – 1523)

- Biagio d'Antonio (1446–1516)

- Pietro Perugino (1446–1523)

- Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449–1494)

- Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519)

- Pinturicchio (1454-1513)

- Filippino Lippi (1457-1504)

- Andrea Solari (1460–1524)

- Piero di Cosimo (1462–1522)

- Vittore Carpaccio (1465-1526)

- Bernardino de' Conti (1465–1525)

- Giorgione (c. 1473 - 1510)

- Michelangelo (1475–1564)

- Lorenzo Lotto (1480 - 1557)

- Raphael (1483–1520)

- Marco Cardisco (c. 1486 – c. 1542)

- Titian (c. 1488/1490 – 1576)

- Corregio (c. 1489 – 1534)

- Pietro Negroni (c. 1505 – c. 1565)

- Sofonisba Anguissola (c. 1532 – 1625)

Depression Countries [edit]

- Hubert van Eyck (1366?–1426)

- Robert Campin (c. 1380 – 1444)

- Limbourg brothers (fl. 1385–1416)

- Jan van Eyck (1385?–1440?)

- Rogier van der Weyden (1399/1400–1464)

- Jacques Daret (c. 1404 – c. 1470)

- Petrus Christus (1410/1420–1472)

- Dirk Bouts (1415–1475)

- Hugo van der Goes (c. 1430/1440 – 1482)

- Hans Memling (c. 1430 – 1494)

- Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450 – 1516)

- Gerard David (c. 1455 – 1523)

- Geertgen tot Sint Jans (c. 1465 – c. 1495)

- Quentin Matsys (1466–1530)

- Jean Bellegambe (c. 1470 – 1535)

- Joachim Patinir (c. 1480 – 1524)

- Adriaen Isenbrant (c. 1490 – 1551)

Germany [edit]

- Hans Holbein the Elder (c. 1460 – 1524)

- Matthias Grünewald (c. 1470 – 1528)

- Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

- Lucas Cranach the Elderberry (1472–1553)

- Hans Burgkmair (1473–1531)

- Jerg Ratgeb (c. 1480 – 1526)

- Albrecht Altdorfer (c. 1480 – 1538)

- Leonhard Beck (c. 1480 – 1542)

- Hans Baldung (c. 1480 – 1545)

- Wilhelm Stetter (1487–1552)

- Barthel Bruyn the Elderberry (1493–1555)

- Ambrosius Holbein (1494–1519)

- Hans Holbein the Younger (c. 1497 – 1543)

- Conrad Faber von Kreuznach (c. 1500 – c. 1553)

- Lucas Cranach the Younger (1515–1586)

France [edit]

- Enguerrand Quarton (c. 1410 – c. 1466)

- Barthélemy d'Eyck (c. 1420 – after 1470)

- Jean Fouquet (1420–1481)

- Simon Marmion (c. 1425 – 1489)

- Nicolas Froment (c. 1435 – c. 1486)

- Jean Hey (fl. c. 1475 – c. 1505)

- Jean Clouet (1480–1541)

- François Clouet (c. 1510 – 1572)

Spain and Portugal [edit]

- Jaume Huguet (1412–1492)

- Nuno Gonçalves (c. 1425 – c. 1491)

- Bartolomé Bermejo (c. 1440 – c. 1501)

- Paolo da San Leocadio (1447 – c. 1520)

- Pedro Berruguete (c. 1450 – 1504)

- Ayne Bru

- Juan de Flandes (c. 1460 – c. 1519)

- Luis de Morales (1512–1586)

- Alonso Sánchez Coello (1531–1588)

- El Greco (1541–1614)

- Grão Vasco (1475-1542)

- Gregório Lopes (1490-1550)

- Francisco de Holanda (1517-1585)

- Cristóvão Lopes (1516-1594)

- Cristóvão de Figueiredo (?-c.1543)

- Jorge Afonso (1470-1540)

- António de Holanda (1480-1571)

- Cristóvão de Morais

Venetian Dalmatia (modern Croatia) [edit]

- Giorgio da Sebenico (c. 1410 – 1475)

- Niccolò di Giovanni Fiorentino (1418–1506)

- Andrea Alessi (1425–1505)

- Francesco Laurana (c. 1430 – 1502)

- Giovanni Dalmata (c. 1440 – c. 1514)

- Nicholas of Ragusa (1460? – 1517)

- Andrea Schiavone (c. 1510/1515 – 1563)

Works [edit]

- Ghent Altarpiece, past Hubert and January van Eyck

- The Arnolfini Portrait, past Jan van Eyck

- The Werl Triptych, by Robert Campin

- The Portinari Triptych, past Hugo van der Goes

- The Descent from the Cross, by Rogier van der Weyden

- Flagellation of Christ, past Piero della Francesca

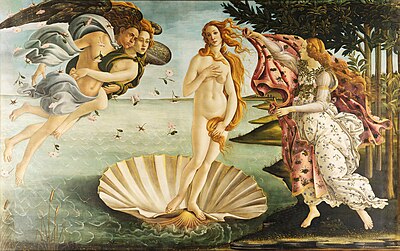

- Bound, by Sandro Botticelli

- Lamentation of Christ, by Mantegna

- The Last Supper, by Leonardo da Vinci

- The School of Athens, by Raphael

- Sistine Chapel ceiling, past Michelangelo

- Equestrian Portrait of Charles V, by Titian

- Isenheim Altarpiece, by Matthias Grünewald

- Melencolia I, past Albrecht Dürer

- The Ambassadors, by Hans Holbein the Younger

- Melun Diptych, by Jean Fouquet

- Saint Vincent Panels, by Nuno Gonçalves

Major collections [edit]

- National Gallery, London, Uk

- Museo del Prado, Madrid, Kingdom of spain

- Uffizi, Florence, Italy

- Louvre, Paris, France

- National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

- Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

- Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, United states

- Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Kingdom of belgium, Brussels

- Groeningemuseum, Bruges, Belgium

- Erstwhile St. John's Hospital, Bruges, Belgium

- Bargello, Florence, Italy

- Château d'Écouen (National museum of the Renaissance), Écouen, French republic

- Vatican museums, State of the vatican city

- Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, Italy

See too [edit]

- Danube school

- Forlivese school of art

- History of painting

- Mughal art

- Oriental carpets in Renaissance painting

- Lives of the Nearly Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects

References [edit]

- ^ "Renaissance". encyclopedia.com. June 18, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "What were the impacts of Renaissance on art, architecture, science?". PreserveArticles.com: Preserving Your Manufactures for Eternity. 2011-09-07. Retrieved 2021-10-19 .

- ^ a b Frederick Hartt, A History of Italian Renaissance Art, (1970)

- ^ Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italia, (1974)

- ^ Margaret Aston, The Fifteenth Century, the Prospect of Europe, (1979)

- ^ https://www.laetitiana.co.uk/2014/07/introduction-to-renaissance-movement.html

- ^ Gardner, Helen; De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard G (1975). "The Renaissance in Northern Europe". Art Through the Ages (6th ed.). New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p. 555. ISBN0-xv-503753-6.

- ^ Gardner, Helen; De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard G (1975). "The Renaissance in Northern Europe". Art Through the Ages (6th ed.). New York: Harcourt Caryatid Jovanovich. pp. 556–557. ISBN0-fifteen-503753-half-dozen.

- ^ a b c Russell, Francis (1967). The Globe of Dürer . Time Life Books, Time Inc. p. 9.

- ^ a b c d Gardner, Helen; De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard G (1975). "The Renaissance in Northern Europe". Art Through the Ages (sixth ed.). New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 561. ISBN0-15-503753-6.

- ^ Gardner, Helen; De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard K (1975). "The Renaissance in Northern Europe". Art Through the Ages (6th ed.). New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 564. ISBN0-15-503753-6.

- ^ Gardner, Helen; De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard 1000 (1975). "The Renaissance in Northern Europe". Art Through the Ages (sixth ed.). New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 557. ISBN0-15-503753-half dozen.

- ^ Gardner, Helen; De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard G (1975). "The Renaissance in Northern Europe". Art Through the Ages (6th ed.). New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 555–556. ISBN0-fifteen-503753-6.

External links [edit]

- The Early Renaissance

- "Limited Freedom", Marica Hall, Berfrois, 2 March 2011.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Renaissance_art

0 Response to "What New Styles of Art Were Developed During the Renaissance"

Post a Comment